Family honors the memory of Patrick McDonald

November 10, 2018, 8:24 am

Kevin Weedmark

This Remembrance Day marks the 100th anniversary of end the of the First World War. Earlier this year the 100th anniversary of the Battle of Vimy Ridge was commemorated, and in August the 100th anniversary of the Battle of Amiens.

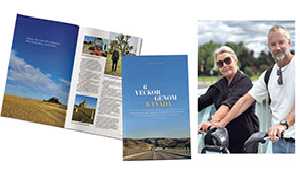

Peggy Kempin and Sarah McDonald marked another anniversary related to the First World War this year—the 100th of the death of their great uncle, Patrick McDonald, in battle.

“I think Sarah and I thought four or five years ago that since it was coming up to the 100th anniversary of the end of the war, and of Pat McDonald’s death, which coincides with the last 100 days of the war,” says Peggy, “we thought it would be a good time to go over there to memorialize him.

“His name was Patrick McDonald. My dad had a brother who was named Patrick McDonald, he had another nephew named Patrick McDonald, and also we have a brother named Patrick McDonald, so the name has been carried on. The name has stayed in the family.”

The family is learning more about their great uncle. “We knew his name was on the cenotaphs at Wapella and Moosomin,” says Peggy. “Just recently it was pointed out that he and three other soldiers are memorialized in a votive candle holder out at St. Andrew’s—I just found that out two weeks ago, so we’re still finding out about this uncle, and the way the community comes together to honor the sacrifices of their citizens.”

How did they start researching the original Pat McDonald? “I just started looking up war records,” says Peggy.

“At first all we could find out was his service number, the day he died, and a very little bit about him.

“When we were looking further, a year later, his portion of the records had been digitized and we could find out more.

“We knew where he had been killed, because we had an uncle who did a family tree and included that information, so we knew which battle he had been killed in—we knew that much.

“We didn’t know a lot but we wanted to find out more with the 100th anniversary coming.”

“I was at Vimy ridge a number of years ago, so I saw his name there,” says Sarah. “It’s one of those things I think every Canadian should see. I’ve had the opportunity to travel a lot, and it’s the number one spot I have ever seen. After I came back from there, Peggy and I talked about going to Vimy Ridge to be there for the 100th anniversary of his passing. He doesn’t have a grave. He is memorialized on Vimy Ridge because that’s where a lot of the soldiers are memorialized who don’t have grave markers.

“Because he died on August 10, that’s the day we planned to be at Vimy Ridge,” says Peggy.

In Amiens and Vimy Ridge, Sarah, Peggy and Peggy’s husband Herb ran into a lot of other families remembering people lost in the war.

“We met a family from Australia who were memorializing their great-grandfather, we met some people from England who were memorializing their great-uncle. The people of France, when they found out why we had travelled there, we were called comrades, we would get kisses on the cheeks and hugs.

“That was a really cool part of the trip, meeting all the other people who had also lost family in the war,” says Sarah. “I wasn’t even thinking there would be other people doing the same thing, but we ran into a lot of them and everyone was so friendly and willing to visit and chat. Everyone was there for the same purpose, to remember someone who had died 100 years ago.”

They ended up visiting many war cemeteries and memorials in addition to Vimy Ridge.

“There are so many cemeteries and they are all immaculate,” says Sarah. “Just pristine.

“All row on row, as the poem says,” adds Peggy. “Everything is lined up perfectly. It literally brings to mind that line, the crosses row on row. And lots of familiar names. McCaws, Treleaven, McDonald, McDougall. I don’t think you need to scratch the surface very hard to find families within Canada that were affected by that war.”

Sarah says Vimy Ridge itself was amazing. “It is awe-inspiring. It is beautiful, it is huge. It’s peaceful. It’s so tasteful. It’s surrounded by the fields and the trenches where the battles took place.”

“It was very emotional. It’s overwhelming because there are 11,000-plus names of Canadian soldiers who that is considered their grave,” says Peggy.

This is the story behind one of those names:

•

It was April 1, 1916 when Patrick McDonald signed up at Moosomin for the 217th Battalion, Canadian Expeditionary Force at the Moosomin Armoury.

He was 19 years old. He had been raised in the St. Andrew’s District.

He was born October 21, 1896, the second youngest child in a family of six boys and two girls.

St. Andrew’s was a district populated by people who moved from Scotaland in the 1880s. In the early summer of 1883—13 years before Patrick was born—a group of 47 Scottish Crofters, from the estate of Lady Gordon Cathcart at Benbecula on the island of South Uist in the windswept Outer Hebrides, arrived in the Wapella district and began the St. Andrew’s Settlement.

Patrick’s parents were John McDonald and Mary (MacPherson) McDonald.

Patrick’s mother Mary passed away in 1902, leaving eight children, including Patrick, age 5, behind.

A photo of the Armory from 1916 helps with picturing the scene when Patrick enlisted.

A massive banner hung across the front of the Moosomin Armory. The banner was so massive, in fact, that it was longer than the front of the Armoury and one end had to be held up by a pole. “Enlist Now 217 Battalion” the massive banner reads.

A smaller “Welcome” banner hangs over the door in a photo from June 1, 1916, two months to the day after Patrick enlisted in Moosomin.

Patrick listed his occupation as farmer when he signed up. He was listed in good health, fair haired, blue eyes, 5’8”.

Before he left for war, he was hospitalized briefly in Moosomin. He was in hospital for 14 days in February of 1917 for Rheumatism.

He was discharged in good health, and on June 2, 1917, he embarked from Halifax on the Olympic.

The Olympic likely made quite an impression on the farm boys who had signed up for the war. It was a sister ship to the Titanic and was used by the Canadian government during the war to transport troops back and forth to England. (The Olympic made headlines during the war, ramming and destroying a German U-boat that was attacking it toward the end of the war.)

He arrived in Liverpool on June 9 or 10 of 2017.

He was posted to the 15th Reserve Battalion on October 14, 1917, and he landed in France on November 9, 1917.

He became part of the First Canadian Mounted Rifles.

He assigned his $15 per month military pay to his sister, Katherine McDonald of Moosomin, who was two years older.

On the second anniversary of his enlistment, he was awarded a Good Conduct Badge in the field.

On August 10, 1918, two days into the Battle of Amiens, he was killed in action. According to his military record, “While advancing with his company over open ground northeast of Bouchoir, he was hit in the lungs by a fragment of an enemy shell and instantly killed.”

The Battle of Amiens was the beginning of the end of the First World War. The “colonial shock troops” from Canada and Australia would lead the charge.

The Battle of Amiens ended on August 11. It was Germany’s worst defeat since the start of the war. In their sector of the attack, the Canadians pushed the Germans back as many as 12 km, a huge achievement in a war often fought over feet and inches. It came at the cost of 1,036 Canadians killed, 2,803 injured and 29 taken prisoner. Overall more than 19,000 Allied soldiers were killed or injured, while the Germans lost more than 26,000 soldiers. The Canadian Corps captured 5,033 prisoners and 161 guns.

When German Kaiser Wilhelm II was informed of what happened at Amiens, he replied, “We have reached the limits of our capacity. The war must be terminated.”

Amiens sparked the Hundred Days campaign, the successful Allied push that would drive the Germans backwards until their ultimate defeat, and result in the signing of the armistice on November 11, 1918, three months after Pat McDonald paid the ultimate sacrifice.

Pat McDonald has no known grave, and is memorialized on the Vimy Ridge Monument, along with 11,285 other Canadian soldiers in the First World War, who were killed in France and have no known grave.

Pat is also memorialized on the cenotaph at Moosomin, the cenotaph in Wapella, and in the tall stone church of St. Andrew’s in the district where he grew up.