September 28, a day in honour of the British Home Children

Over 100 years more than 100,000 children were sent to Canada to serve as farm labour. One woman wants more people to know their story.

September 23, 2024, 10:25 am

Ashley Bochek

Over the course of a century, more than 100,000 British Home Children crossed the Atlantic Ocean from London, England to Canada.

The children were sent to Barnardo Homes in England to help relieve financial stresses of young British families in the 1800s.

The children were sent to Canada through the Barnardo organization. Parents were unaware until returning to the homes to find their children, that the children had been sent to Canada.

Debbie Bochek, a descendant of a British Home Child, explains her family's connection to this little-known part of Canadian history.

“In the 1800s in England after the Industrial Revolution, a lot of farm families were moving into the cities for jobs, and as they moved into the cities it resulted in overcrowding and overpopulation. A lot of families then were having trouble supporting all of their children and it became a time of poverty. So, children ended up living on the streets and it was a problem in the cities—in London, in particular.

“Then, England came up with the idea where they would ship over young children to Canada because Canada was a young country at the time, and Canada could use young children to learn how to farm and be adopted out to families.

“So, it helped both countries. This movement lasted for around 100 years of these children coming to Canada and about 100,000 children were sent to Canada over the 100 years from the mid-1800s to mid-1900s.”

Bochek says each child had a trunk to travel from England to Canada.

“It was Dr. Thomas Barnardo that came up with this idea to house these children over there, and then came up with this plan to send them to Canada. When each Barnardo child came to Canada they had a trunk with specific items in there—not a lot. They weren’t allowed to bring any personal items I think just to try and sever the ties and not be missing their families at home so there were no dolls, or toys, or photographs in their trunks.”

She says the children didn’t find out about their parents until later in life. “A lot of the children were told they were orphans, but many found out later that they did have at least one parent still living over in England.”

Family Connection

Bochek says her great-grandpa was sent to live in a Barnardo home at a young age.

“My great-great-grandmother was a single parent—her husband had passed away when my great-grandpa was two months old. She had four boys then and she couldn’t look after them all. Then, she started sending them out to the Barnardo homes not all at once, but I know my great-grandpa ended up in what was called Babies Castle in Hawkhurst, a part of London which is still under Barnardo Homes. She ended up sending all four of her boys to Barnardo homes and in the end all four boys ended up coming to Canada.”

She says the children were sent on ships to Canada and sent to Barnardo homes across the country.

“My great-grandpa came over with a brother of his. My great-grandpa was Albert Edward Gurr and he came over in 1897 with his brother, Amos Abel Gurr. My great-grandpa was nine at the time and his brother was 11. They came over on a ship called the SS Labrador that left from Liverpool. There were over 100 children that came over at that time and they arrived in Quebec City. In time, my great grandpa and his brother came by train to Manitoba. They were sent to live at the Barnardo farm at Russell. In Russell, these boys would learn to farm. They had all aspects of farming there, they had chickens, pigs, dairy, and horses, they learned inevitably how to farm. Then, from Russell, once they turned 18, they were placed on farms. My great grandpa was placed near Beulah, Manitoba and his brother was placed near Miniota.”

“I remember growing up, my mom would talk about her grandpa and I was always interested in my family history,” Bochek said. “I never met my great-grandpa Gurr, so whenever asking my mom questions she always said she felt bad because he never really talked about it.”

She says some British Home Children were treated poorly in Canada. “A lot of those children when they came over to Canada they were meant to feel shame, and a lot of them weren’t treated very well, some were, but more and more in different non-fictional books that I read, I've learned most of them weren’t treated overly well.”

Can find out online

Anyone can look up their last name on an online website to see if they have a connection to a British Home Child.

“There is a website online called the BHC registry,” Bochek said. “I just type in British Home Children and the website that comes up—anyone can go on there and type in a last name and it will give you a list of anyone with that last name or a similar spelling because sometimes the ship manifest—the spelling gets misconstrued so you can look and see. I can type in Gurr, and then find my great grandpa and his brothers when they came and what ship they were on.”

Bochek says her family is still in contact with relatives of her great-grandpa’s brother.

“The other two brothers that came over didn’t end up coming to Manitoba, they ended up in Ontario and from any research that has been done, they never married and so the family tree on their side ended with them coming, but then at Miniota and Hamiota, my great grandpa and his brother, I have done quite a bit of research and they had families of their own. My mom is often in contact with relatives from Miniota.”

Home Children’s story not part of Sask curriculum

Bochek, a teacher at McNaughton High School, says she is surprised it is not in any social studies textbooks for students to learn.

“I think for 100 years of Canadian history, not a lot of people are aware of it unless it is a part of your family. I am proud to be a descendant of a British Home Child. I'm proud of all they survived, all they went through, I'm proud of their strong work ethic, and their will to persevere through all those hard times.

“As a teacher too, I am surprised it doesn’t seem to be in textbooks for Canadian history. I do teach in my classroom about Truth and Reconciliation, Residential Schools, and how they lasted around 100 years and these British Home Children were coming over for about 100 years as well, and I feel that it needs to be recognized too.”

Bochek says the story of the British Home Children is more known in Eastern Canada.

“It is bigger in Ontario because that is where a lot of the children came. I find in Saskatchewan it doesn’t seem to be as well known. I have talked to some teachers in Manitoba and have heard it is touched on a little bit in their curriculum.”

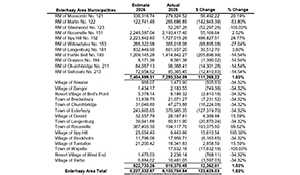

The Barnardo homes in Canada

Bochek says the Barnardo home in Russell housed a lot of British children.

“The Barnardo Home in Russell housed about 100 children. As more came in the older ones left, but I know I have researched, and at 5:30 am they woke up to a bugle and religion was a big part too. They had a service every day. Then, they did chores for a lot of the day. This house had so many rooms. I have been to Russell and gone to the site. There are no buildings, but there is a sign with a picture of the home, and information about the farm. Not far from there is a cemetery because some children passed away over all those years and buried there, but it is not big. I have gone back and paid tribute to great-grandpa.

She says she has read a lot of books pertaining to the history of British Home Children.

“I have read a lot of books about the British Home Children and the Barnardo Homes. The stories that I have heard from the Barnardo children being here at the homes are mainly the negative ones.

“Some of the stories are very sad, for example a boy who comes to Canada and lives in a barn, eats out of a pig trough, eats dog scraps out of a dog dish, but they’re not all like that. My mom said her grandpa never really talked about it and I think it maybe was because it wasn’t a positive experience.”

Once the Home Children were adults they were to leave the Barnardo Home in Russell.

“Once the Barnardo children turned 18 they were on their own,” Bochek said. “My great-grandpa settled in the Hamiota area and his brother in the Miniota area.”

Bochek says the brothers didn’t know how close they settled to one another until eventually meeting up at a community gathering.

“My great-grandpa and his brother did come in contact at one point after leaving the Barnardo home and settling on farms. I believe the story goes that they met up one time at the Birtle Fair, and got talking and realized how close they were. Then, every Sunday after that they were done chores, they would walk and meet half-way, have a picnic, and then they would go back in time to do chores. It is special when you think about it.”

Little known Canadian history

Bochek says she is unsure why the story of the British Home Children isn't better known.

“I am not sure why more people don’t know about it. If there is something more that I could try to do to, to get the story out there, I would love to.

“I think in Manitoba it is almost a bit more known maybe because of the Russell Barnardo home for boys,” Bochek said. “I am on a couple groups on Facebook, I just try to learn more and I teach it to my students so they learn about it because it is important, and part of our Canadian history.”

Embracing British Home Children

Bochek takes pride in wearing the colours to represent the British Home Children on the day set aside to honor them.

“On September 28, when it is British Home Child day I do make a point of wearing my red, white, and blue to school, and telling my students about it.

“It encompasses red and white for Canada and our flag, and the red, white, and blue of the Union Jack for Britain.”

Bochek reads a book on Home Children to her students.

“I read a novel to my students every year called, Home Child, and they absolutely love it. I have been reading it now to them for a few years. The story in the book makes me think of my great-grandpa coming to a farm and working hard on the farm.”

Bochek says she has had students in the past who know about their own family’s history and connection with British Home Children.

“I have had two students in the past that knew they were British Home Children descendants, some were Isabelle and Bodie Tilley, and Sully McGonigal. They have brought in some of their memorabilia and then we can look up on the website and find their ancestors. It is neat and exciting and then if they go home and they’re excited, and it gets their parents excited or they ask their grandparents more, it is a start.”

She says there were other organizations sending children to Canada at the time. “A lot of the children are referred to as Barnardo children even though they might have been under another organization because there were so many Barnardo children. They kind of are synonymous even though they might not have been directly a Barnardo child, there were other organizations too.”

Good intentions

Bochek believes the Barnardo organization had good intentions sending the children to Canada and housing them until they were 18.

“I think they had the best intentions. The Canadian families did pay them so it was very much part of the government and it did help both Britain and Canada.”

Gurr family reconnects

Bochek says her great-grandpa’s mom ended up coming to Canada later in life to reconnect with her sons.

“For my story I can say there was a bit of a happy ending because my great-great-grandma in England, she did eventually come to Canada and meet up with all of her boys, and I think a lot of stories wouldn’t have ended that way.

“In England, she eventually remarried, she was a housekeeper, she wouldn’t have been educated. After her second husband passed away she came to Canada and met up in Ontario with one son there, Alfred. There is documentation that she came out to Manitoba so she would have met up then with my great-grandpa, Albert, and his brother Amos, and actually at that time, it is believed that Edgar, one of the other brothers, was living with Amos on the farm at Miniota. So she would have probably caught up with all of them. She stayed in Canada after that and is buried in Orangeville, Ontario.”

Sunflowers represent British Home Children

Bochek says the sunflower symbolizes the British Home Children.

“The sunflower represents British Home Children. When I see the sunflower now it has a whole new meaning for me," she says.

“Sunflowers are bright and inspire hope, British Home Children came to Canada hoping for a brighter future. As the sunflower grows the flowers face the sun beginning each day in the East and ends each day in the West. British Home Children got off their ships in the East and most travelled West into all parts of Canada. Sunflowers are very strong and can endure various environments. British Home Children had to be strong mentally, physically, and emotionally and endured various living situations. Sunflower seeds are encased in shells, most British Home Children kept their life stories to themselves encased in their hearts.

“I think that is very true. It absolutely encompasses what a home child is and what a sunflower is. I find it neat too because now my mom uses sunflowers as her centrepiece on her table in the kitchen now that she knows.”

Farming in Manitoba

Bochek says her great-grandpa learned to farm at the Barnardo home in Russell before farming his own land near Hamiota.

“My great-grandpa did eventually farm on his own. He married my great-grandma and they had a lot of children. They farmed in the Hamiota area and when they retired they moved to Brandon, and they’re buried there.”

Bochek says they have never seen her great-grandpa’s trunk from when he came to Canada.

“I am wishing I knew where his trunk ended up, but I am wondering if it was maybe something he didn’t care to keep if it wasn’t a positive experience for him. I never met him, but I did meet my great-grandma. They had a good life together.”

Extended family connections

Bochek says the Gurr family at Hamiota is still in contact with the relatives in Miniota.

“It makes me wish that we knew more of great grandpa’s story and when my grandpa Gurr was alive, I wish I had asked him more questions because I think as a son, he may have known more as well, but of course at that time in my life it was not something that I was as interested in as I am now. That is what I wish, that I could have learned more back then or even ask my great-grandma when she was alive. I am sure she would have known some stories.”

Bochek says a family friend had done a lot of research into the Gurr family tree.

“A good mutual friend of all of ours from Hamiota, Donna Sararas has done a lot of research on the Gurrs for her friend at Miniota, and so she has gone back as far as the parents of my great-grandpa, so my great-great-grandpa and grandma who sent them over. Great-great-grandpa passed in July of 1888 after my great grandpa was born in April of that year. So we have back as far as that. .

She says the Gurr family has no information on where the one brother ended up.

“The one brother, Edgar, we have lost track of. We don’t know where he is buried, and being the oldest we think he was very transient and couldn’t settle anywhere for very long.”

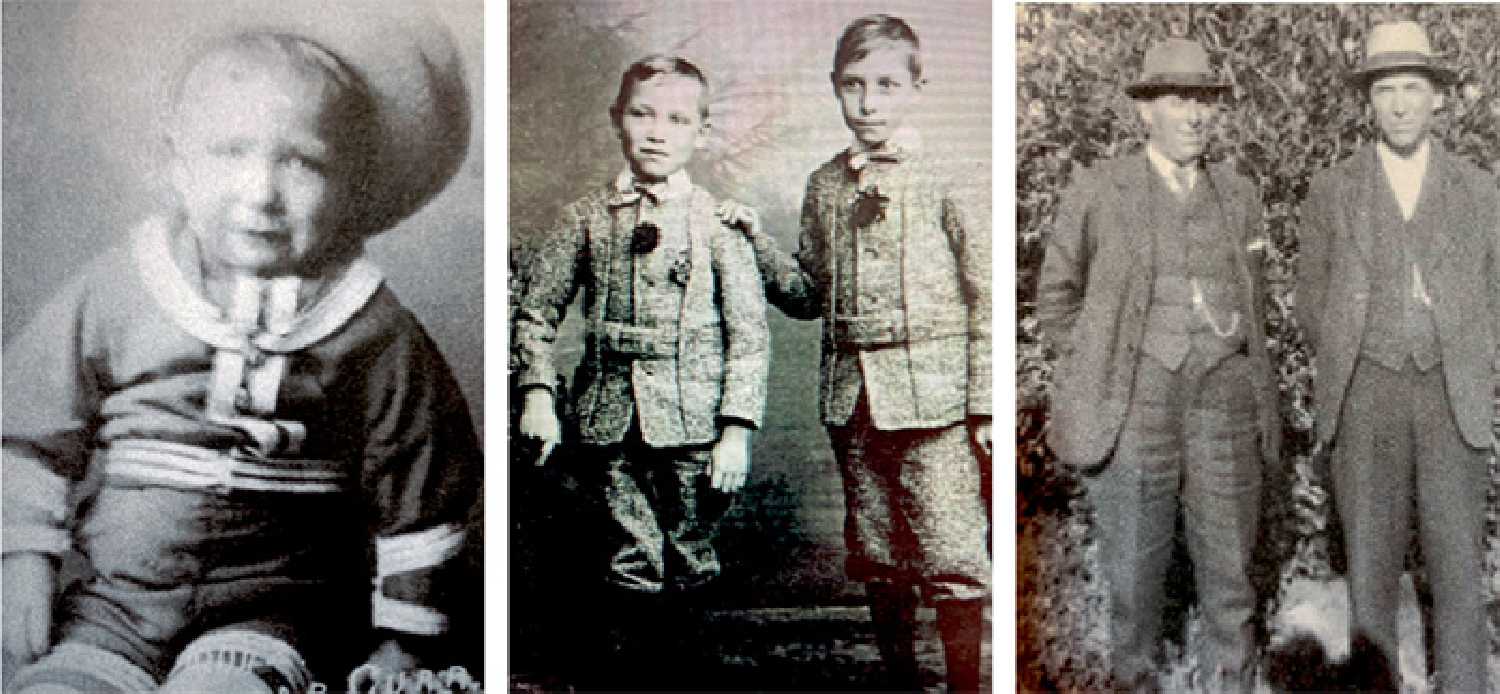

The Gurr family has pictures of the brothers.

“I was able to get some pictures too so that was special, but there are only pictures of the three boys, Alfred Gurr, there was no picture of him,” Bochek said. “We also wondered how we would even find pictures because they weren’t allowed to bring their own personal belongings, so we think when their mom came over from England she brought them with her. I think it is too bad—probably a lot of moms who sent their children to these Barnardo homes in England and they were told and promised that they would see their children some day trusted that, and a lot of them never did and those children just ended up thinking that their parents passed away.”

Bochek says her great-great-grandma sent the boys to Barnardo homes thinking she would one day pick them up.

“I believe that it is just the fact that when she had these four boys and my great-grandpa was born and then two months later her husband passed, there was no way she could work and look after four young boys and so she turned to Barnardo homes. My great-grandpa was the last one she sent to a Barnardo home because he was the youngest. The Barnardo homes were for destitute children. The parents would send them there to be looked after and they were believed to think once they could get on their feet they could go there and pick their children up, but when they went to pick them up, they found the children had already been sent to Canada.”

September 28 known in other parts of Canada

Bochek says different monuments in other parts of Canada portray the colours of British Home Children in honour of their journey to and life in Canada.

“On the British Home Children Day there are different monuments all over Canada that use red, white, and blue lights on that day to commemorate the British Home Children. The Calgary Tower, Niagara Falls, and the CN Tower are all lit in red, white, and blue. There was a stamp at one time for the British Home Children in 2010. There is also a monument at Pier 21 in Halifax, but my ancestors came to Quebec City.”

Proud to be a British Home Child descendent

Bochek says she is proud to be a descendent of a British Home Child and wants to continue to learn more about the historical movement.

“I find it very special. I think that is part of me. I feel that I am hardworking like them, and I want to learn more about my family and what they went through. I think of it as a big part of me.”

Bochek says it is important to know your family’s history.

“It is who you are. It is important to know your roots and be proud of what your ancestors have accomplished and gone through. It makes you, you.”

Bochek is sharing her story and connection to British Home Children to let people learn and look into this little-known episode in Canadian history.

“I want people to know that it lasted a long time and maybe if you’re a British descendant, you might want to do a little bit of digging and find out if you’re a descendant of a British Home Child as well. I think that is special and it means a lot. It is a pretty unique story.” Tweet